Southeast Asian nations are increasingly facing a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors,1 which in turn correlate with a propensity towards cardiac-related diseases including heart failure (HF). In Singapore, HF is the most common cardiac cause of hospitalisation, accounting for 17 % of all cardiac admissions2 In 2015, public hospitals recorded in excess of 5,700 unique HF admissions.3 The objectives of this paper are to describe unique transitional interventions used in our programme to reduce HF readmissions, to discuss the impact of resource utilisation, and draw comparisons with published literature on transitional care (TC).

Scope of the Problem: HF Hospitalisation and Readmissions

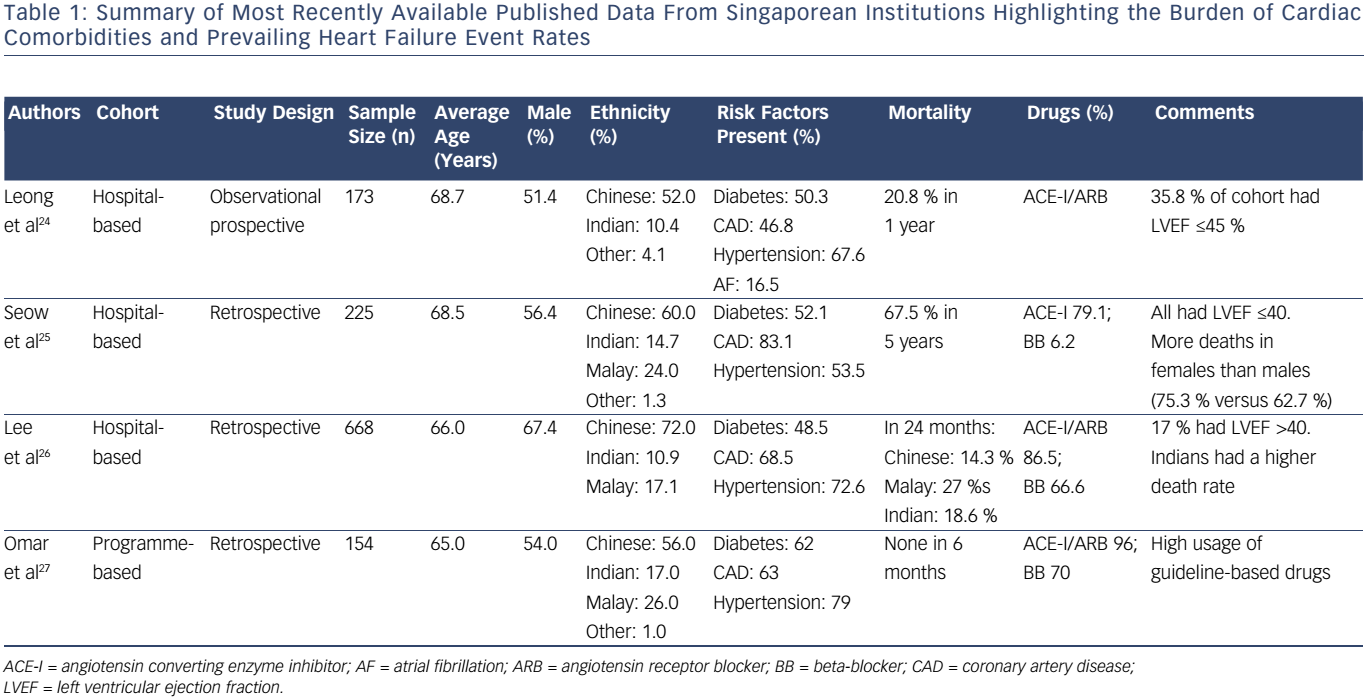

Ng et al. reported a rising trend in incident HF admissions among those aged >65 years between 1991 and 1998, the final 3 years showing an acute rise, with admission rates per 10,000 population rising from 85.4 in 1991 to 110.3 in 1998.4 Subsequent publications from local institutions have highlighted the current burden of cardiac comorbidities and prevailing HF event rates (Table 1).5 –8 The mean ages of HF patients in these publications ranged from 65.0 to 68.7 years. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (48.5–62.0 %), hypertension (53.5–79.0 %) and coronary artery disease (46.8–83.1 %). By 2014, pooled data from three public institutions in Singapore showed that HF readmission rates were 18 %, the average length of stay was 5.2 days per admission, and in-hospitalisation mortality was 4 % (unpublished source).

TC Models in HF

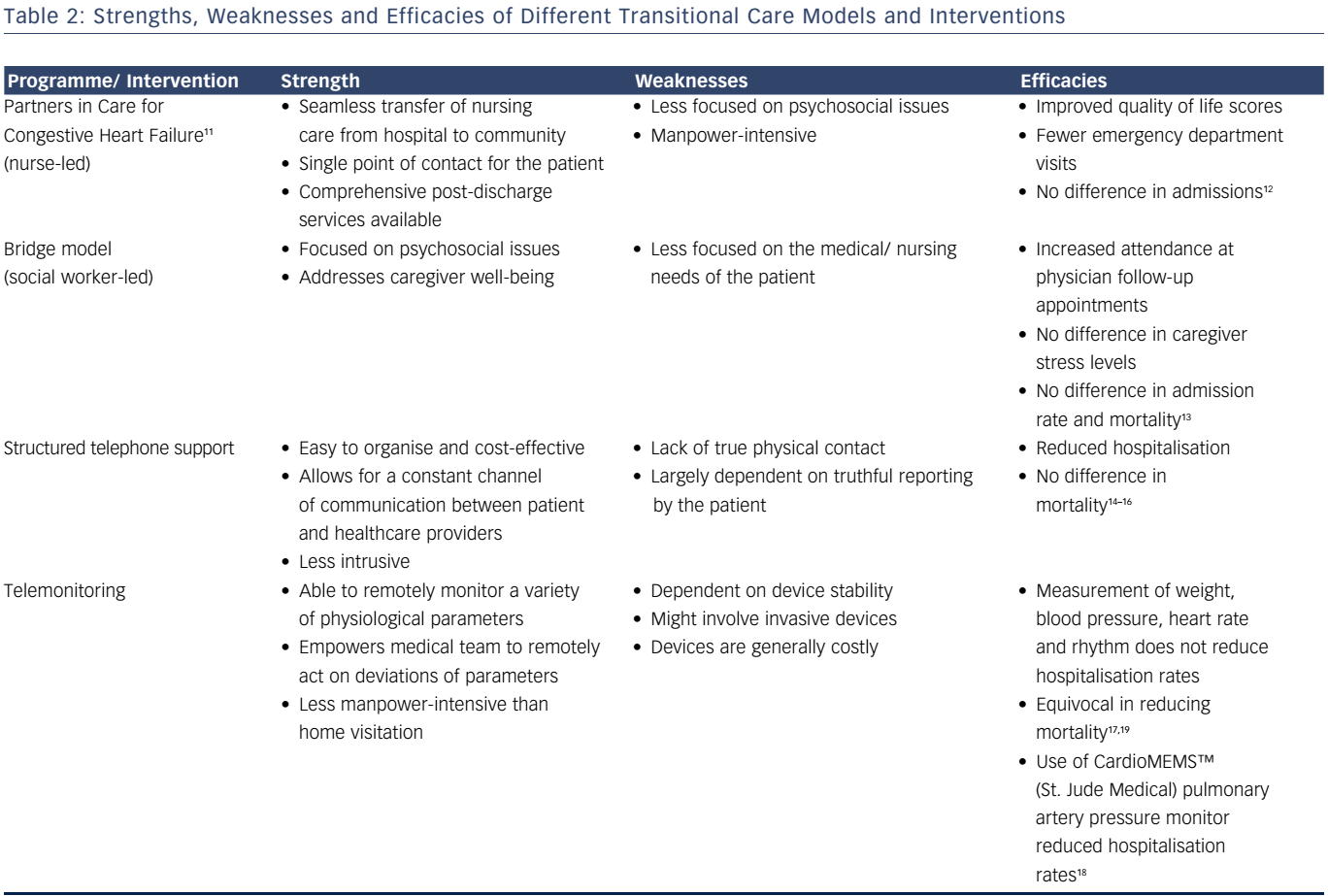

There are multiple challenges in caring for patients with advanced cardiovascular diseases.9 Unmet needs in this group affect readmission rates. The role of TC is to bridge gaps in patient management during the transition from acute hospital care to home and community care. A review of existing, varied TC programmes revealed common intervention themes and strategies, including early admission assessment, medication reconciliation, patient education, caregiver inclusion, telephone follow-up, home visits, handovers to post-hospital care providers and early follow-up.10 Nurses are the main healthcare providers in most TC models. Table 2 shows the strengths, weaknesses and efficacies of the different TC models and interventions.11 –19

Nurse-led TC Programme

The Canadian Partners in Care for Congestive Heart Failure model evaluated the efficacy of a TC programme on top of the usual posthospital care to improve patients’ quality of life and reduce readmission rates.24 In this model, TC nurses provided further services to cater to unmet needs, utilising: supportive care for self-management; links between hospital and home nurses; and balance of care between patient, family and professional care providers. Patients were given a comprehensive workbook and educational maps, providing patients and their caregivers with knowledge about post-discharge selfcare. They were also provided with information and resources to formulate systems for social/community support. Prior to discharge, the TC nurse sent a nursing transfer letter to the community nurse, highlighting the patient’s clinical status and management needs. A routine post-discharge phone call was also made by the TC nurse to check on progress.

The strengths of this programme lies in patient/caregiver empowerment and the provision of a single point of contact (the TC nurse), should the need arise. It also provides smoother transfer of care from hospital to the community. This model is manpower intensive, however, with less focus on patients’ psychosocial issues. Patients being managed under the TC programme had better Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire scores and significantly fewer emergency department (ED) visits at 6 and 12 weeks post discharge. There was a trend towards fewer patient admissions under this TC programme.

Social Worker-led TC Programme

The bridge model, devised by the Illinois Transitional Care Consortium, is a social worker-led, post-discharge intervention programme targeting unmet biopsychosocial needs.12 In a randomised trial conducted by the Consortium, the TC programme, termed the Enhanced Discharge Planning Program (EDPP), was compared against usual care for patients with high social risks for readmission. On top of regular hospital care, patients on the EDPP underwent detailed psychosocial assessment as inpatients. Patients’ post-discharge care needs were identified and relevant community partners and resources were identified and engaged prior to discharge. A postdischarge phone call by the EDPP social worker was made on the second post-discharge day to check on the patient’s progress.

This social worker-led model has a strong emphasis on psychosocial issues, even addressing caregiver well-being but provides less focus on medical and nursing needs than the nurse-led programme. Patients on the EDPP were more likely to return for scheduled physician follow-up appointments; however, there were no statistical differences in patient/ caregiver stress, readmission rates within 30 days and mortality.

Structured Telephone Support

Structured telephone support (STS) involves contacting the patient after discharge to provide them with continuing education on his or her condition, assess symptoms and check on medication compliance. According to the DIAL trial, a randomised trial of telephone intervention in HF, patients in the STS arm were less likely to die from or be admitted for HF compared to patients receiving standard care.13 A Cochrane review on the effect of STS intervention including 16 trials involving 5,613 patients showed a significant reduction in HF admissions but a non-significant reduction in mortality rates.14 A separate meta-analysis of 13 randomised STS trials, however, showed a significant reduction in mortality rates for HF patients receiving STS over standard care.15

The strengths of STS lie in its ease of organisation and costeffectiveness. It allows for a constant channel of communication between the patient and healthcare providers, without being as intrusive as home visits. The drawback is that there is a lack of true physical contact and information is largely dependent on truthful reporting by patients or caregivers.

Telemonitoring

With the advancement in remote monitoring technology, telemedicine has emerged as a key player in the field of post-discharge care. Telemonitoring has the ability to remotely monitor a variety of physiological parameters, empowering healthcare providers to remotely act on deviations of parameters.

In the Trans-European Network-Home-Care Management System trial, telemonitoring was shown to reduce 1-year mortality rates; however there was no effect on hospitalisation rates.16 In the Telemedical Interventional Monitoring in Heart Failure trial, patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II/III HF were stratified into two groups: physician-led remote monitoring or standard care. The trial did not show any difference between the two strategies in relation to improving mortality or hospitalisation rates.17 The invasive Chronicle® device (Medtronic Inc), which was implanted in the right-hand side of the heart to measure right ventricular pressure, was not approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration as the Continuous Haemodynamic Monitor in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure (COMPASS-HF) trial did not show a reduction in HF events in the device group.18 However, in the CardioMEMS™ Heart Sensor Allows Monitoring in Pressure to Improve Outcomes in NYHA Class Heart Failure Patients (CHAMPION) trial, active titration of diuretic doses based on pulmonary artery pressure readings transmitted by the CardioMEMS device was associated with decreased rates of hospitalisation.19

The drawbacks of telemonitoring include the cost of monitoring devices, dependence on device stability and lack of direct contact with the patient. This limits communication to address psychosocial issues with patients and caregivers.

Regional Experience in TC

Efforts to implement TC in the management of HF patients are uncommon in Asia. A recent randomised trial of a nurse-led TC programme for HF patients in Hong Kong demonstrated no significant differences in event-free survival, hospital readmission or mortality between the TC and usual care groups.20

Current Recommendations

Both the American College of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology recommend effective systems of care coordination to provide HF patients with comprehensive multidisciplinary care plans from the beginning to the end of their healthcare journey.7,8 In the scientific statement from the American Heart Association,23 effective care coordination requires the optimisation of communication among healthcare providers in multiple disciplines, identifying patients at high risk of unfavourable outcomes, adequately training the healthcare professionals involved and assessing health-related quality of life measures to enhance the psychological and social support available to patients. Quality improvement strategies are also important to improve and integrate the work processes involved in care coordination.23

Local Institutional Experience and Evidence

A TC programme for HF patients was initiated at our institution in April 2014. The purpose of the service was to enable the smooth transition of care plans from hospital discharge to home and to improve patients’ medical, functional and social care status in the community setting post discharge.

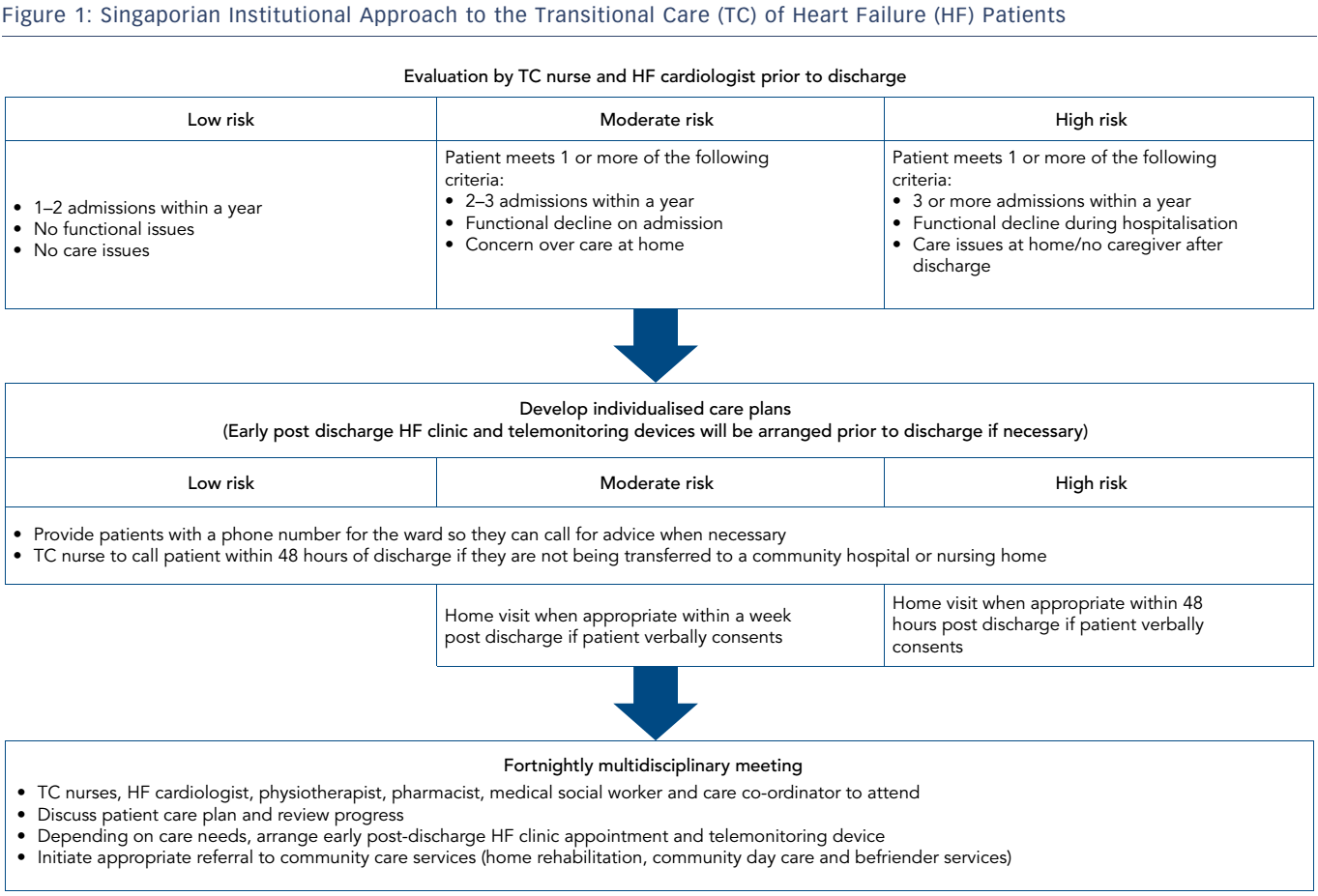

TC was applied to newly-diagnosed HF patients, those with recurrent readmissions, as well as HF patients experiencing functional decline or social issues. Patients were risk-stratified into low, moderate or high risk of post-discharge readmission depending on the number of readmissions in a year, degree of functional decline and level of care support (Figure 1). Care components of the HF transitional service include: post-discharge telephone interviews and hotline; nurse-led home care visits; early post-discharge HF clinic; and telemonitoring of weight with medication titration.

Care components are individualised to patients’ care needs depending on their risk groups. Not all HF patients enrolled in TC receive all care components.

In order to correctly titrate patients’ medication, patients who are likely to clinically benefit from weight monitoring are supplied with a weighing machine on discharge. This remote monitoring system transmits readings to the hospital’s database. Weight monitoring is also offered to patients in the outpatient clinic who do not require other TC interventions, such as home visits. The nurses review the readings daily and titrate diuretic dosages based on the readings and telephone communications of each patient’s clinical condition.

All patients on the programme who are at moderate or high risk have their status reviewed during a fortnightly multidisciplinary meeting. Following this, their care plans are adjusted according to their needs.

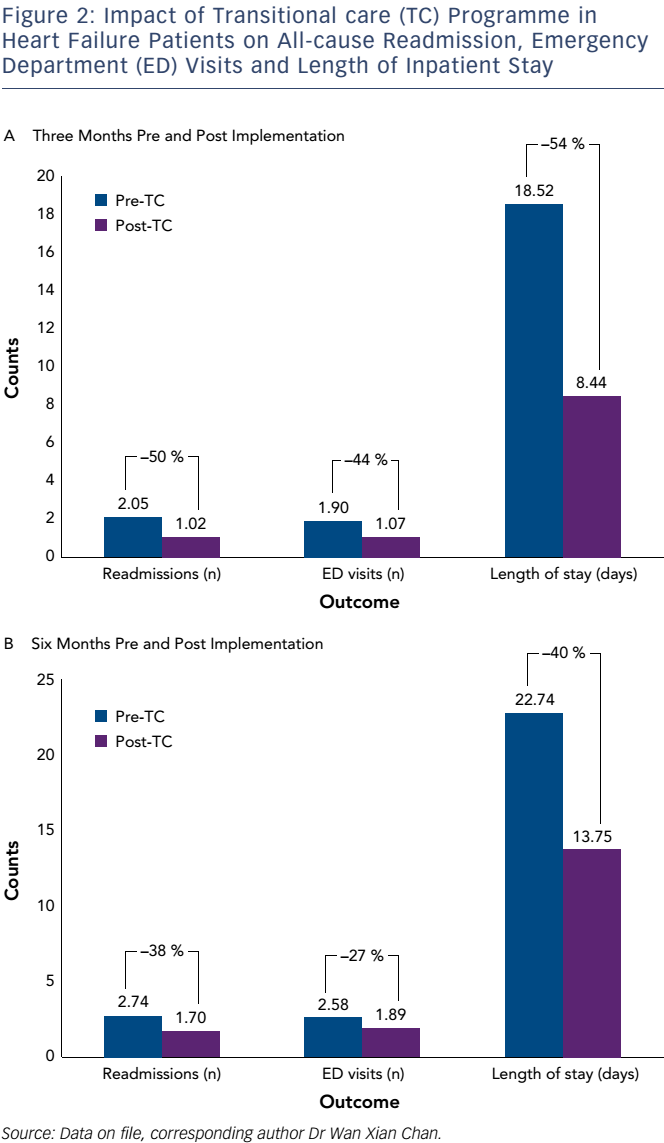

Our programme enrolled 60 HF inpatients and nine outpatients between April 2014 and September 2015. We observed a 50 % decrease in readmissions, 44 % decrease in ED visits and 54 % reduction in length of stay when we compared these parameters 3 months before and after HF TC management (Figure 2a). The decrease in readmissions (−38 %), ED visits (−27 %) and duration of hospitalisation (−40 %) was sustained 6 months after enrolment for the 53 patients remaining in the programme (Figure 2b). By then, seven patients had been discharged from the TC programme. For the remote weight monitoring intervention, which included the outpatients, there was a significant reduction in HF readmission (−31 %) and duration of hospital stay (−31 %) for the 6 months post-recruitment.

Implications for Future Practice and Research into HF Care

TC is important in the provision of patient-centric, coordinated care meeting the multi-faceted needs of HF patients. Current HF TC practices, interventions and patient populations targeted are heterogeneous, however, and no clear guidelines for clinical applications can be drawn from existing data.17 Research into interventional TC models should enhance and augment the delivery of care to provide consistently good clinical outcomes in a cost-effective manner. Patient-centric outcomes, such as quality of life, functional status and patient satisfaction, are important to patients and caregivers and further research efforts are needed within the wider context of the healthcare system. As effective transition of care should aim to reduce societal costs, the cost-effectiveness of and cost-savings introduced by TC models are important outcomes to evaluate. The application of innovative technologies in HF care started with telemedicine using remote monitoring technology8 and pulmonary artery-guided management with a wireless implantable haemodynamic monitoring system.13 Further research into and applications of innovative technologies could augment current HF TC strategies.

The future of TC programmes in HF clearly lies in a multidisciplinary approach with:

- nurse-led structured telephone support combined with home visits (scheduled depending on patients’ and caregivers’ needs);

- general physician-led remote medical consultations to adjust medications and care plans (to address functional and psychosocial issues);

- multidisciplinary support from medical social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians and pharmacists, depending on patients’ care needs;

- the application of remote monitoring devices, if applicable;

- the involvement of community care services (community or home rehabilitation, home nursing care, home hospice care) to support patients’ care needs in the long term.

The coordination of care for HF patients and caregivers encompassing hospital discharge and holistic management at home as well as the employment of community care services to meet care needs is required. This could potentially reduce HF hospital admissions, improve patients’ quality of life and satisfaction with care, and empower patients to make self-care decisions.

Conclusion

Published data from institutions in Singapore5–8,24 suggest that incident admissions due to HF in Southeast Asia are rising, and patients admitted for HF are younger with higher mortality rates. Conversely, there is an urgent need to improve quality of care throughout the continuum of the disease, with its unpredictable trajectory of clinical events and multidisciplinary care needs. Through the implementation of transitional HF care in our institution, we reconstructed the care coordination and workflow pathways, overcame barriers that disrupted seamless care delivery, and optimised health system operations.

TC in this patient group requires patient-centric, multidisciplinary care coordination from hospital to home to community in the longterm, applied in a cost-effective manner and enhanced by the use of innovative technologies. Further research is needed to augment current TC practices.